|

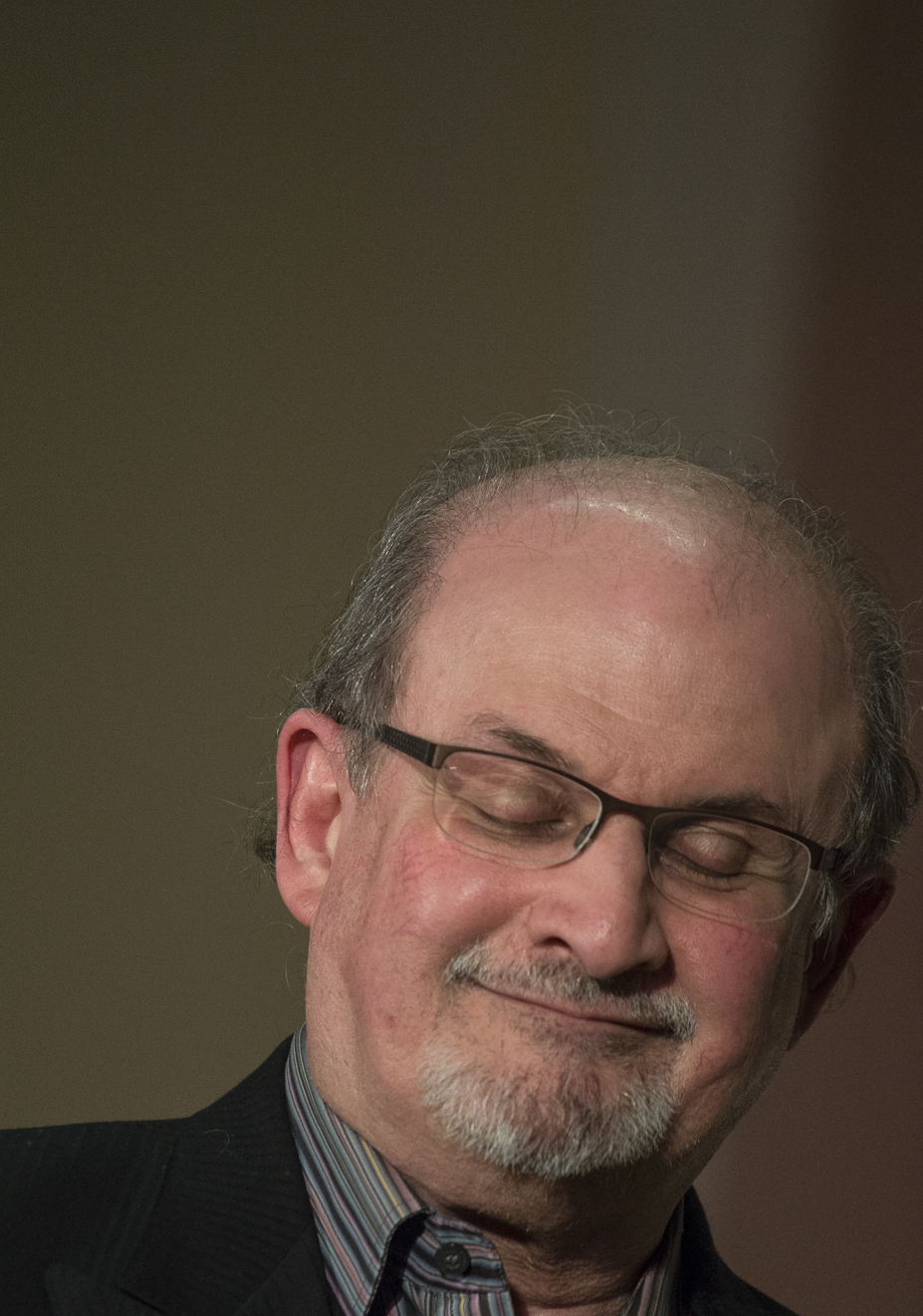

A week after two gunmen massacred staff at the offices of the Paris-based satirical magazineCharlie Hebdo, author Salman Rushdie came to Vermont on a bitterly cold January day. He’d been invited to give a speech for Vermont Reads, a Humanities Council program that annually selects one book—this year, Rushdie’s Haroun and the Sea of Stories—to spark statewide discussion.

In the question period that followed his talk, Rushdie was asked about Charlie Hebdo. Below is a response in which he shares his hard-won insight into the clash of satire, free speech, and religion. Rushdie spent years in hiding, under police protection, after Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, then the Supreme Leader of Iran, issued a 1989 fatwa against him. Essentially an assassination order, it condemned Rushdie for blaspheming Islam in his novel The Satanic Verses, which included a less than hagiographic portrayal of Muhammad.

Most of Rushdie’s formal talk at the University of Vermont concerned the first book he wrote after the fatwa, Haroun and the Sea of Stories. Although the tale was meant to please his young son, many of the book’s themes are dark and deeply political, with added resonance after the Paris murders. Intertwined in Horoun’s fabled world is a struggle between defenders of speech and those who try to strangle it. The silent villain of the book, and perhaps the embodiment of censorship, is Khattam-Shud, whom Rushdie describes as “the Arch-Enemy of all Stories, even of language itself. He is the Prince of Silence and the Foe of Speech.”

Although his position is somewhat nuanced, Rushdie sees religion as playing a similarly oppressive role. “Religion, he wrote after the Paris murders, is ”a medieval form of unreason, [that] when combined with modern weaponry becomes a real threat to our freedoms. This religious totalitarianism has caused a deadly mutation in the heart of Islam and we see the tragic consequences in Paris today.”

In an interview with Vermont Public Radio, Rushdie spoke to the conflict between church/mosque and free speech: "The victory of the French Enlightenment was a victory over the church and not the state. And out of that came the modern idea of free expression. So now you could argue that we're having a similar battle but different religion, different church, but same argument.”

Asked about the role of satire, Rushdie told the packed house at the University of Vermont:

“If you are a writer, it’s kind of like if you’re a composer, you would have an orchestra to compose for, and sometimes you write more for the strings and sometimes more for the keyboard, and you don’t have to write for the same thing every time you compose. In the same way when you’re writing, you don’t always write for the same part of the orchestra. And so satire is one of the tools and it’s a very important one. And actually in the history of France, it’s been enormously important ever since the French Revolution. Some of the first really powerful satirical pieces in the French history were fuilleton, the sheet that was distributed in the street, attacking Marie Antoinette after she encouraged people to eat cake, which was very bad for their health. So there was a kind of early gluten-free satire at that time.

“The French satirical tradition has always been very pointed and very harsh. And still is, you know. And the thing that I really resent is the way in which these, our dead comrades, these people who died— using the same implement that I use, which is the pen or a pencil—have been almost immediately vilified and called racists and I don’t know what else. Which is a dreadful crime against their memory.

“And I didn’t know them well, but I met Stéphane Charbonnier, the editor of Charlie Hebdot—[a person]less racist than whom it would be hard to find. For starters, I mean, there might be other things wrong with him: He was a communist; he was a communist member of the far left in France and to describe him as a rightwinger is a bizarre description.

“But you know Charlie Hebdot attacked everything. It attacked Muslims, the pope, it attacked Israel and rabbis, it attacked black people and white people, and gay people and straight people. It attacked every kind of human being. It was what? It was making fun. Its strategy was to make fun of people. And it was seen as that. It was seen as that. It was very beloved. Its cartoons were very beloved in France. [Slain cartoonist] Wolinski, the old gentleman of 87 years old, he was a grand old man of French culture.

“So anyway, the thing that I come to—I used this phrase on TV the other day— the rise of the ‘but-brigade.’ I got so sick of the goddamn but-brigade. And now the moment somebody says ‘Yes I believe in free speech, but,’ I stop listening. ‘I believe in free speech, but people should behave themselves.’ ‘I believe in free speech, but we shouldn’t upset anybody.’ ‘I believe in free speech, but let’s not go too far.’

“The point about it is, the moment you limit free speech, it’s not free speech. The point about it is that it’s free. Both John F. Kennedy and Nelson Mandela, in important speeches, used the same three-word phrase which to my mind says it all: “Freedom is indivisible.” You can’t slice it up. Otherwise it ceases to be freedom.

“And you can dislike Charlie Hebdot. You know, not all their drawings are funny. You can dislike, but the fact that you dislike them has got nothing to do with their right to speak. The fact that you dislike them certainly doesn’t in any way excuse their murder. And the idea that within days of this murder, sections of the left as well as the right have turned against these, these fallen artists to vilify them is, I think, disgraceful. The end.”

|